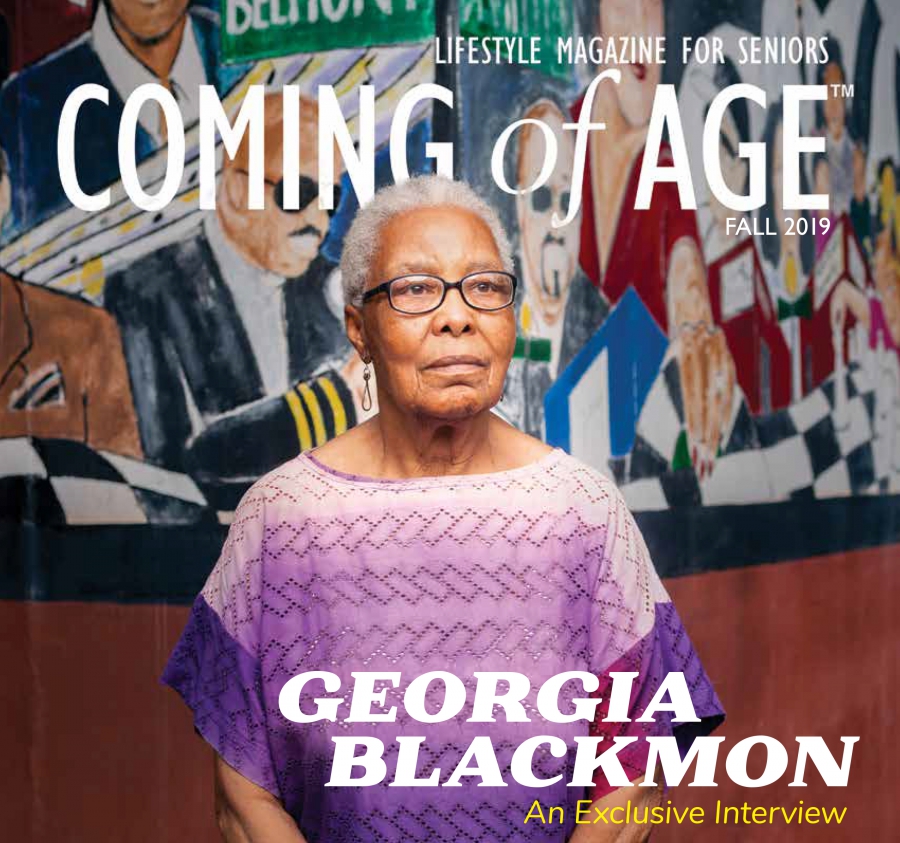

When local Pensacolians picture Georgia Blackmon, her signature locks, which she grew for more than 30 years, often come to mind. You’ll notice those locks are gone in our cover photo of Mrs. Blackmon. “It was time for a change,” Blackmon said. The 78-year-old Pensacola native has changed more than her hair in recent months. Deciding it was time to retire, late last year, Blackmon closed the bookstore she opened in 1989. The Gathering Awareness and Book Center served as both a bookstore specializing in African-American literature and history and a community gathering place that offered a welcoming spot for the community to gather, talk, learn and grow.

Blackmon also founded Mother Wit, a 501(c)3 focused on two agendas: community outreach and education for children and historic preservation. Mother Wit’s current preservation project is the restoration of the Ella Jordan House, which was built in 1890 and used for decades as a teaching center for the black community, a center for voter registration and a meeting space for a variety of organizations including the Colored Women’s Foundation. Mother Wit is restoring the house for use as a museum that will commemorate Ella Jordan’s impact in our community.

Coming of Age had the pleasure of talking with Mrs. Blackmon about her upbringing, her passion for community and her marriage of 57 years.

Hi Georgia, thanks for taking the time to talk with me today. Let’s start by talking a little about your childhood and upbringing.

I was born in Pensacola, but I went to Camden, Ala. when I was about six years old. My mother had five other children who were older than me and she had to work, so I went to live with my grandmother and my great-grandmother right there at the Alabama River and it was awesome. The closest house to me was five miles. I thought that was fun because I had these two old people there with me. A lot of people ask me questions today, but it took me a long time to understand that by being raised by these old people with nobody else around me—no other children around me—I was a kind of an old soul. I was different even in school. One of the things that I am thankful for is that I did not allow the bullying at that time and being different to change the way I thought.

So they instilled some some self-awareness.

Oh, they instilled things that I still use. A lot of times I was grown before I really understood what they were saying. Two of the things that always stayed with me that they said were, “Tongue and teeth fall out. You bite your tongue, but just because you bite your tongue you don't pull your teeth” and she said that “If you follow someone going nowhere, you'll go nowhere with them,” so always be very of careful who you hang out with. It was good advice.

Did they instill your love of literature or did you find that on your own or somewhere else?

No, I have to give my husband credit for that. I came from a poor family and my husband came from kind of a middle class family. And so he was accustomed to reading. I wasn't. The only thing that we had in our house was a Sears and Roebuck book and things like that. When he and I got together in our 20s—we've been married for 57 years—he started reading to me. He read that first book to me—I never shall forget. The first one was Manchild in the Promised Land and the next one was Richard Wright's Black Boy. The third one was the Autobiography of Malcolm X. When he got to that, I was on my own. I was reading for myself.

How did you two meet?

My husband was a football player. He got a scholarship to Southern University and he was a ladies’ man. He really was. The ladies were just crazy about him. I think we met at a going together party and I didn't stay. The lady that I was with stayed in the party, you know, we were in high school. He came outside and tried to talk to me and I just kind of ignored him. The next time I saw him, we were living in the same apartment complex and he came up and started talking. So we got together.

Do you have children?

Two children, five grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. My daughter has one child and she lives in Valdosta. She's in education. My son lives here and he has four sons. His children have their own children. My oldest grandson has two and my second grandson has one.

What's different for you about parenting versus grandparenting or great-grandparenting?

One of the things for me is that I came up in a village. I really did. The church, the community and the teachers worked together as one. So we were trained and taught that we were capable of doing anything that we could imagine from all three of those places on the same line. They would tell us to reach for the moon. You might land among the stars, but reach. That's where Mother Wit came from. The older people that I was around used the phrase Mother Wit and it meant you were smart. They would say, “That gal got mother wit. That boy got mother wit.” So that's how the naming came about. The generation that I came up in was different. The time I came up in—it wasn’t just black people that were poor. It was poor across genders and race in the neighborhood that I came up in. I live in the same house that I came up in as a child. Across the street there was a man named Mr. Bob who happened to be white. Mr. Bob would bring all the children in the neighborhood—black and white to his house once a week and he would teach us games and stuff. Mrs. Bob, she would come out when he finished and she would bring us cookies and Kool-Aid.

It seems that there used to be more of that—going to neighbors houses and hanging out and just knowing them more than we do now.

There was. I really truly believe that somewhere along the line we lost our way. See, I think what people fail to believe is that like it or not, we are all one. I'm going to say a poem to you that I believe:

"God of love, forgive—forgive Teach us how to truly live

Ask me not my race or creed, Just take me in my hour of need And let me know You love me, too, And that I am part of You.

And someday man may realize That all the earth, the seas, and skies Belong to God who made us all—The rich, the poor, the great, the small—And in the Father’s holy sight

No man is yellow, black, or white. . . And peace on earth cannot be found Until we meet on common ground And every man becomes a brother Who worships God and loves each other" —Helen Steiner Rice

I believe that with all my heart. The older I get, the more I know. I think if we could just come to that as a people, all of this hate in the world will disappear. If we could just come to understand that we are one—we are all connected. And even if we don't come to that understanding for ourselves, we could look at coming to that understanding for the next generation and the children. They need to know that.

How are you feeling about the current state of race relations in America and in politics?

I cry. I'm 78 years old and what I know about myself and the things I’ve learned along this journey is that that's not the way. It's not the way and it never will be the way. I might not ever see the change, but I know that's not the way. So what we have done—there’s a group of us across race and gender that have come together and we work with children across race and gender. We bring them together and they work together and get to know each other. They put on a program about three or four times a year. They’re going to put one on somewhere around the Christmas holiday. Last year we had the program at the United Methodist Church downtown. There wasn't anybody on the program but children. Susan Polis Schultz wrote a poem called "One World, One Heart, One Moon after 9/11. And so we had the children write an essay on that.

I think the question that you asked about what is going on now—I think it's there to let us see, and some of us don't see it, that we are all connected and we need to work together to make things better for unborn generations. We are just one people.

We go to Selma for the bridge crossing every year. There was a white lady that was killed there and her family still comes. There's a young man, young white man from Michigan who brings a busload of his students every year. I'll be honest with you, I go for the energy. Yes. It's such a good energy up there across race and gender—it’s almost like you forget race when you go there. It's so different. I told my husband Johnny, I said, “We have to go because I need that energy. That energy gives me the energy for the year when I come back to Pensacola.” It's good.

When did you come back to live in Pensacola from Alabama?

I started school here. I think somewhere around the second grade. I went to J. Lee Pickett. I started off at Spencer Bibb, but it was over crowded so we were going to a couple churches. When J. Lee Pickett was built, we went there. Then I went to Booker T. Washington High School.

Did you go back to Alabama?

Every summer, but that was not my choosing. You see, my grandmother farmed. So she had three daughters. My mother had the most children—she had seven. My other two aunts had two apiece. When school was out for the summer on a Friday, all the cousins were in Alabama on Sunday to help gather those crops. I had to pick the cotton, the peas and the peanuts. We were there for the whole summer, you know, but it was also good. It was good to just be there with my cousins and all. Again we were right on the Alabama River and that was beautiful.

What did you do after high school?

Well, I met Johnny and we got married. I worked at Carmen Daniel’s dress shop for about six years. Matter of fact, I was a part of the march against segregation in downtown Pensacola. I was already working and I was a maid. With that march, the maids that were working down there became the first sales associates. And so that's how that happened. I left Carmen Daniels and went to Judy Leslie at Cordova Mall. I stayed there for maybe about five years and then I left and I went to McRae’s. I was a sales associate there for 19 years. When I left there, that’s when I opened the bookstore.

What was your inspiration opening the bookstore?

The bookstore is the Gathering Awareness and Book Center. It is the gathering of peoples in awareness of mind. It specialized in African-American history and self-awareness. What really made me go into it is when we would go to Atlanta or even down to Tallahassee they had black-owned bookstores and that was the only place that I could find black books, so I thought we need a black bookstore here. So that's what I did. I started out—I wanted a black bookstore that specialized in books about African-American history and selfawareness.

My husband has taught me to listen. So I was talking to my pastor about what I wanted to do and he brought his wife. His wife is a lot like me – we are both very strong-minded, strongwilled. And so I was sharing with him what I wanted to do and I couldn't understand why he brought his wife. So she says, “It amazes me how people always want to give you what they think you need instead of what you want.” I started to come back at her and the Spirit said, “Be quiet.” So about two weeks later, the Spirit woke me up with what she had said and I thought, “Hmm, What people want.” And the churches came up. What kept the bookstore open was the service we did to the churches. It allowed me to do the other stuff that I wanted to do. You see, the church is going to always need their communion. They're going to need their Bibles, their hymnbooks, their Sunday school books. So serving the churches enabled me to do the other stuff I wanted to do.

When you closed it, did you consider passing it down or selling it?

I tried that. I wanted that so bad. I think that it served a purpose here. I think that it would be good for it to go on and I tried that, but I couldn't get anyone to see that. My children, that's not their mindset. It’s not my children’s dream, it’s mine. They’re happy with what they're doing.

What do you think about the growth and development in Pensacola particularly in Belmont Devilliers where your bookstore was located, and downtown in general?

As a matter of fact, we just had a guy come up and speak on the importance of African American history because the Ella Jordan house is going to be the Ella L. Jordan African-American Museum. Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois both said, “If you don't know your history, you're doomed to repeat it.” So, it is important that we keep that history—not just for us but for our children, our grandchildren and for everybody. I need to know your history. You need to know mine. We need to know because we are all in this universe together. What I see in Belmont Devilliers, my thing is that people do not allow the history to disappear. So my thing is that you have so much African American history in here. You want everybody’s history, but African-Americans cannot afford to lose their history. They need it for their children and grandchildren.

So that's what we want to do with the Ella Jordan house because that house was built in 1890. Mrs. Ella Jordan bought it in 1929. You just think about that and those women and the things that they did there. Booker T. Washington’s wife came to that house. Mary McLeod Bethune came to that house. Eleanor Roosevelt came to that house. They had different clubs there. They had their Top Leaders of Distinction. They had the Colored Women Federated Club.

The universe belongs to everybody and you need everybody’s history. Your children need to know all history and how it happened. You know what I'm saying? I think Belmont Devilliers has a good toehold on it and I pray that they don't let it go.

We have a good oversight committee with the Ella Jordan house so it will be there. We have Mrs. Barnes who runs the John Riley Museum in Tallahassee. She's guiding us all the way. We're just really excited about what's going on. We're looking at being open either the latter part of this year or the first of next year. You’d be amazed at how many people across race and gender wanted us to just knock it down. When we got started with this, they said in order for it to stay historical, it would cost $362,000. We owe a little bit over $100,000 now. But let me tell you something—like I tell people, I’m not religious—but God has brought people together across race and gender to save that house.

How can the average citizen still help?

They can still donate money. They can make the check out to Mother Wit and note the Ella Jordan House in the memo. Donations can be sent to P.O. Box 2054, Pensacola, FL 32513.

So you mentioned the inspiration for the name Mother Wit. Tell me a little bit about when and why you started the foundation.

The foundation was started in 1996 and became a 501(c)3 in 2005. Now the other part away from the Ella Jordan house is focused on working with children 13 and up. Every second Saturday from 11 until 12:30 we do Tomorrow's Leaders Preparing Today. We have speakers come before them to tell their stories. I think our second speaker was Bentina Terry. We rotate male and female speakers. Then, we do Party for a Purpose. That's when the Center for Disease Control comes in. So many young people 13 and up were getting infected with HIV. So Center for Disease Control started party for the purpose. We have a speaker for 30 to 35 minutes, we feed them and we have a DJ until 11 o'clock at night. We do that every 90 days. We also take them on a trip. We took them to New Orleans, we took them to Selma and we took them the Gulfarium.

You recently cut off your signature dreadlocks, which was a surprise for a lot of people. How long did you have them?

Well, I had a big Afro in the 1960s. It must be over 30 years because I was selling books and I was reading the information on the locks. And then I read the story. A lot of people call them dreadlocks and this book was saying they are Nubian locks. The word dreadlock came from negative people. I read that book and I thought I want to try that. There was a young couple here. They came out of Atlanta. He was a barber and she was a beautician and so that's how I got started. I loved it, but it was time for a change.

Let's talk about Pensacola as a community and what it means to you having been born and raised here.

I was born and raised here and I love it. I have no desire to go any place else. Whenever I travel, it’s always good to come home. Pensacola has a have a lot of good people across race and gender. If you are a human being you

2025 Council on Aging of West Florida

P.O. Box 17066

Pensacola, FL 32522

Phone: 850-432-1475

Homemaker and Companion AHCA Registration #4941

United Way Partner Agency

HIPAA Notice • Privacy Policy

Council on Aging of West Florida is compliant with the Better Business Bureau's Wise Giving Alliance Standards for Charity Accountability. Learn more at www.bbb.org.